|

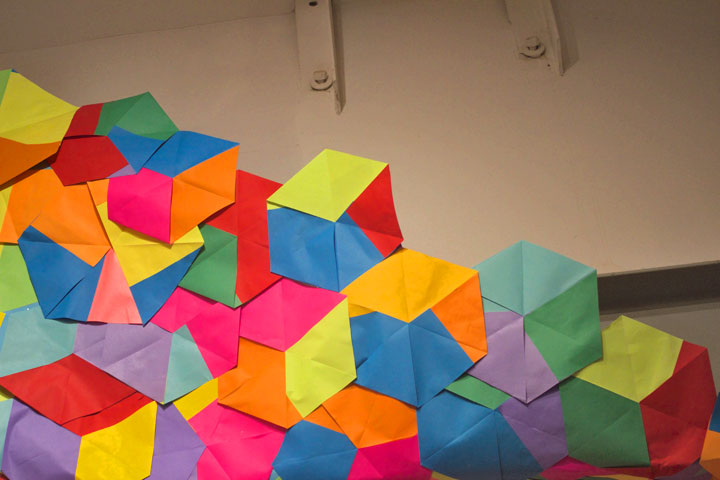

Blanche Descartes, [You're so Square] Baby I Don't Care, 2015 |

|

As a visual artist Rebecca Niederlander roves across numerous disciplines, equally in her element working as a digital artist, sculptor, ceramist, fabric artist, and installation artist; it follows that the range of materials she uses in her studio practice is similarly eclectic, including digital prints on vinyl scrim, an array of metals, clay, string, electrical wire, cloth, theatrical lighting gels, zip ties, and anything else that is effective for a given work. But she has a special af nity for paper, a favored medium that she returns to again and again for the myriad forms this protean material can assume. Niederlander’s three-dimensional works are never discrete, self-contained, autonomous objects that occupy a given space in a predetermined way. Rather, they evolve through an indefinite—and potentially infinite—series of repetitions, each building on the previous one, inching, spreading, and nally sprawling, in ts and starts, wherever they want to go. Even if their nal forms in a gallery are circumscribed by limits of available space, production time, or budget, the process of their fabrication declares—virtually shouts—that they could continue far beyond what is being displayed. They imply their own infinitude beyond the here and now. Niederlander accomplishes this metaphysical leap of faith through manifestly physical, and physiological, references and processes. To begin with, in her paper projects, she often composes at a cellular level: that is, she settles upon a given unit or building block of composition-it could be a paper strip, or a loop made of a paper strip, or any single example of a paper shape—to which she then adds another and another and yet another, growing the object like a living organism. Botanical forms—striking sculptural evocations of buds, leaves, owers, petals, roots, branches—or other biomorphic forms resembling networks of neurons or ganglia pervade her paper works. Characteristically, they gather in masses and clusters that expand rhizome-like—that is, they extend out like an underground root system, sending out shoots almost anywhere. The endless connections, interceptions, overlaps, and mergers that define the growth patterns of Niederlander’s paper works are suggestive of not only the patterns of the physiological development of any living being but (by the extension of our focus on our own humanity) also of the aesthetic/intellectual/ spiritual evolution and transformation of our individual selves, values that Niederlander pursues in both her art and her personal life with a devotion not unlike a religious calling. For example, her 2014 project, What Do I Care? Part 1, engaged a group of college students to anonymously write down a secret thought on a square of vellum paper which they then folded into the form of a small three-dimensional box and left in the gallery. Eventually the boxes numbered in the thousands, with contributors left to re ect on the innermost thoughts of their fellow anonymous participants, whose thoughts might be anybody’s— or everybody’s. For her site-specific project in this Paperworks exhibition Blanche Descartes, [You’re So Square], Baby I Don’t Care (2015), Rebecca Niederlander specifically sought out a challenging, irregular, architectural oddment in the Craft & Folk Art Museum’s third- oor gallery space: a permanent, low-to-the- oor, triangular display platform with its own overhanging roof and an adjoining wall that wraps around to the entry to the gallery, where her paper “organism” shares wall space, and interacts with, the exhibition's title signage. Her objective for her site project, and whatever qualities it may acquire as it evolves in situ, is to have a totally symbiotic relationship with its setting. from the Paperworks catalogue essay by Howard Fox |  |

| |

|

|

| |